Answer songs have come a long way since Bear Cat meowed itself into a lawsuit by the authors of Hound Dog and caused Sun Records to sell Elvis Presley’s contract to RCA.[1] Today, they are a staple of the music world, from Sabrina Carpenter’s Skin clapping back at Olivia Rodrigo’s Driver License for the latter’s calling out a certain blonde femme fatale, to Nicki Minaj’s Anaconda echoing Sir Mix-a-Lot’s Baby Got Back from a female point of view.[2] Miley Cyrus’ Grammy-winning Flowers has long been speculated to be a direct response to Bruno Mars’ When I Was Your Man, as it provides point-by-point retort to every regret (“should have/would have”) expressed by Bruno’s male protagonist.[3] A recent lawsuit tests whether Miley’s inspiration went too far and ventured into the forbidden copyright infringement territory.[4] For record labels and their artists everywhere, we take a look at the line drawn between tributes and illegal borrowing, straightforwardly termed as the “fair use” defense.

The Flowers Allegations.

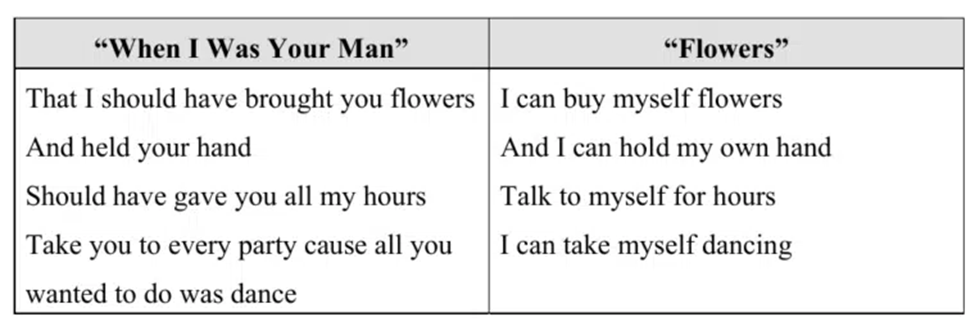

While Bruno Mars is not a claimant in this lawsuit, the right holders claim that the lyrics in Flowers bear a “meaningful connection” to Bruno’s song, and this connection is so substantial that it cannot be coincidental.[5] The lawsuit also claims melodic similarities; however, it is the alleged lyrical “meaningful connection” that is at the heart of the lawsuit.[1] As alleged, the following lyrics infringe Bruno’s song:

The lawsuit claims copyright infringement by unauthorized copying and public performance, as well as unauthorized distribution, licensing, sale and other exploitation of Bruno’s lyrics. It cites the public’s immediate recognition of “the striking similarities between the song[s],” as supposedly confirmed by the press commenting that “the similarities between the two songs have been identified by many, and that ‘any listener can detect that … [Bruno’s] song boasts a chorus that is the inverse of what Cyrus sings on ‘Flowers.’”[1] Interestingly, it points to the boost in streaming of Bruno’s song upon Flowers’ release, credited to “the ‘chatter over the relationship between the two songs,’ including speculation by fans that Flowers was inspired by When I Was Your Man….”[2]

Is Miley’s Use Fair?

Fair use is “an equitable rule of reason that permits courts to avoid rigid application of the copyright statute when, on occasion, it would stifle the very creativity which that law is designed to foster.”[1] Given the quintessentially transformative nature of Miley’s answer song, her use will most likely prove “fair” to beat the infringement allegations. In fact, it is difficult to imagine a more transformative use than her female point-by-point response to a list of male relationship regrets.

“[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, … for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching …, scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.”[2] Fair-use factors include: “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”[3]

Notably, it is the last factor that is “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use” because it strikes at the heart of the policy served by the Copyright Act.[4] Recall that the Flowers plaintiff claimed a boost in sales due to the allegedly infringing song. Does it mean that the Flowers plaintiff has now admitted in its very complaint that it cannot possibly satisfy the market harm, the “single most important” element of fair use? That would be a fair argument, pun very much intended.

In any event, in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is the relevant jurisdiction for this lawsuit, transformative use under the first factor usually wins the day.[5] “The central question … is whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original …, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character. The larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use.”[6] While a derivative work’s commercial nature generally weighs against fair use, “the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”[7]

In other words, the more one’s work transcends the original, the fairer the use will be. As the Supreme Court recently underscored, the Copyright Act is here to promote creativity above all.[8] Accordingly, the litmus test for fair use is “whether the copier’s use fulfills the objective of copyright law to stimulate creativity for public illumination.”[9] As long as the alleged copier “adds something new and important,”[10] the use is fair as a matter of law. Miley’s answers to Bruno’s questions are thus as close to a textbook case of fair use as anyone’s use can get.

[1] Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 593 U.S. 1, 18 (2021) (internal citations omitted).

[2] 17 U.S.C. § 107 (emphasis added).

[3] Id.

[4] Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539, 565 (1985).

[5] See, e.g., Seltzer v. Green Day, Inc., 725 F.3d 1170, 1177-79 (9th Cir. 2013) (Green Day’s use of art in concert video was fair because the images were presented with “fundamentally different aesthetic”); Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 508 F.3d 1146, 1164-68 (9th Cir. 2007) (search engine’s use of thumbnail images was fair use because it was “highly transformative…. Just as a parody has an obvious claim to transformative value because it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one, a search engine provides social benefit by incorporating an original work into a new work, namely, an electronic reference tool.”) (internal citations omitted); Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corp., 336 F.3d 811, 818-20 (9th Cir. 2003) (use of exact replicas of artist’s photographs as “thumbnail images” in a search engine was transformative because their purpose was completely transformed from their original use as fine art); Mattel, Inc. v. Walking Mountain Prods., 353 F.3d 792, 796-98 (9th Cir. 2003) (concluding that photos parodying Barbie by depicting “nude Barbie dolls juxtaposed with vintage kitchen appliances” was a fair use); Los Angeles News Serv. v. CBS Broad., Inc., 305 F.3d 924, 938-39 (9th Cir. 2002) (inclusion of copyrighted clip in video montage, using editing to increase dramatic effect, was transformative); Fisher v. Dees, 794 F.2d 432, 436-40 (9th Cir.1986) (song parody was fair use).

[6] Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. 508, 510 (2023).

[7] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 579 (1994).

[8] Google, 593 U.S. at 18.

[9] Id. at 29 (internal citations and alteration omitted).

[10] Id.

[1] Tempo Music Compl., at ¶ 4.

[2] Id. at 2 n.1.

[1] Purely lyrical copyright infringement cases are relatively rare. The undersigned author has litigated one of the most publicized lyrical infringement cases involving Taylor Swift’s hit Shake It Off and its lyrical sequence “players gonna play, haters gonna hate.” See Hall v. Swift, 782 F. App’x 639 (9th Cir. Oct. 28, 2019), as amended and superseded by, Hall v. Swift, 786 F. App’x 711 (9th Cir. Dec. 5, 2019); Hall v. Swift, 2021 WL 6104160 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 9, 2021).

[1] https://www.americanbluesscene.com/2014/03/blues-law-hound-dog-vs-bear-cat/.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Answer_song#cite_note-1.

[3] See id.

[4] Tempo Music Investments, LLC v. Miley Cyrus, et al., Case No. 24-CV-07910 (C.D. Cal., Sept. 16, 2024).

[5] Id., Compl. at ¶ 56.